Hi everyone

Well we've just completed the most arduous section of our trip so far, crossing the Democratic Republic of Congo: the first tourists to do so in at least 2 years. Unfortunately, this country has virtually no infrastructure: no roads, no postal service, no phones and definitely no Internet or e-mail.

So the message below spans over two months.

After sorting out a few details the two of us and our newly acquired travel companion, Joe, left Nairobi, taking the overnight bus to Kampala, Uganda. We arrived in Kampala around mid-day and headed off to the backpacker's lodge. The owner of the lodge gave us an inkling into what we could expect in Congo (the former Zaire) when he told us about 6 guys who had attempted the same trip a few months before and had been arrested as mercenaries and deported. He also claimed that there were 4500 rebels in the jungle who were about to overthrow a paranoid Kabila. This view was contradicted by local truckers who claimed that trucks were crossing from Kampala to Kisangani (central Congo) in a week without any problems! Both sources were very wrong.

The night before we left Kampala we partied huge with half a dozen other backpackers in Kampala's various chic night clubs until 4am and then slept for a few hours before catching the morning bus to the Uganda/Congo border. We arrived in the border town of Bwera - the site of horrific massacres by the Ruwenzori rebels a few months before - and camped the night there.

The next morning we walked the 4km from Uganda to Congo: our home for the next two and a half months.

At Kasindi, the Congolese border town we were met by wonderfully helpful and efficient border officials who speedily processed our documents which gave us hope that finally this country had shed it's notoriously corrupt and incompetent government officials. Unfortunately these hopes were completely unfounded as you will read later.

After waiting a few hours we hitched a lift on top of a large truck on its way to Beni, 80km away. It may give you an idea of how bad the roads are in this country if you consider that it took us 9 hours to complete the 80km journey: and this was definitely the best road we saw in our first month in the country!

The state of the road was compensated for by the incredible landscape. We first crossed the magnificent, snow-capped Ruwenzori mountains ("the Mountains of the Moon") famous for their breath-taking beauty and incredible fertility (bamboo grows one meter a day a here!). We then descended into the outer edges of the mighty rain forest that was to be our home for the next three months. The road deteriorated drastically with mud holes everywhere as the jungle thickened steadily: massive trees laden with vines lining our route.

At around 8pm we arrived in Beni where we were immediately confronted by a screaming, machine gun-toting soldier who seemed about to execute us but, in fact, was telling us to report to the local immigration office the next day. A Military Intelligence official then led us to a grassy patch where we could camp which, we discovered the next morning, was in fact the city's main traffic circle.

The next morning, after being reprimanded by the immigration official for camping where we had, we found a hotel where we could pitch our tent. We then headed off to the civil intelligence department where we were told that we couldn't climb the Ruwenzori's due to rebel activity there. Disappointed, we set about searching for trucks heading into the jungle.

We managed to arrange a lift quite easily and were set to leave the next morning. Unfortunately then the military arrived at our hotel and caused us all sorts of hassles. They claimed that their landrover was also heading to Mambasa, our destination, and the commander offered us a lift which promised to be much faster and more comfortable than the truck ride we'd arranged. Naturally this all turned out to be a lie and the military's web of lies eventually kept us in Beni for a week during which time we were searched and Dave had to intervene physically to prevent the drunk commander from executing a 12 year-old kid for theft when in fact all the kid had done was talk with us.

Eventually we managed to sneak out of Beni on the back of a bakkie (pick-up) with 10 other passengers on our way to Mambasa. This road took us into the heart of the jungle, surrounding us with enormous trees and dense foliage, broken every 20km by tiny villages of pygmies and other tribes. The road deteriorated into mud hole after mud hole which took its toll on our vehicle which broke down 11 times and took two days to complete the 150km journey.

Eventually we arrived in Mambasa where we camped for free in a local hotel's grounds. The next morning we were hit for various bribes by immigration officials which we politely and firmly refused. In Congo, unlike any other country in the world, there are immigration offices in every town and city where tourists are forced to report and have all their details recorded (and have bribes demanded of them). In some towns we were forced to report to three different bureaus who each recorded the same information.

Eventually we were finished with all the bureaucracy and were lucky to catch the truck that goes to Epulu twice a week. After 7 hours on 70km of terrible road we eventually made it to the small town of Epulu, insignificant other than for its population of weird Okapi's. These animals look like a cross between a giraffe and a zebra and are the size of a large horse. We camped in the Okapi Reserve alongside the spectacular Epulu River and were taken on a guided tour into the rainforest to look at about 20 of these shy animals.

One of the bizarre-looking Okapis, Epulu, DR Congo

Sunset, Epulu, DR Congo

We spent three days in Epulu swimming in the river and collecting supplies for the next, arduous stage of our journey. In order to cross the Congo from East to West, we needed to reach Kisangani, the large port town on the banks of the dark Congo River. Unfortunately the first 225km of the road from Epulu to Kisangani, once known as the trans-African highway, is now only a muddy path through the forest, only two feet wide in places. Trucks occasionally try this suicidal road every now and again but can easily take longer than 3 months to complete the 120km stretch to Nia Nia and none attempt the road from there on to Kisangani where we were heading. The only supplies the jungle villages receive are brought by bicycle traders. These guys push and ride their single-gear bikes over 600km carrying up to a 100kg of supplies.

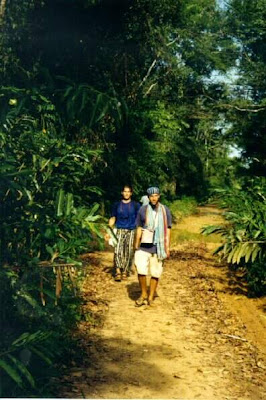

We decided to hire two young bicycle traders to carry our backpacks and food supplies and we set off on a two week walk of 225km through the jungle.

Only 220km to go! Lance and Joe, Dem. Rep. of Congo

This may take a bit longer than we expected... DRC

We walked 20 to 30km per day camping in the tiny, palm-fringed villages along the way. The villagers were naturally shocked to see the three of us marching along and received us with wonderful hospitality. We invariably camped free in the chiefs compound and were helped with cooking every night. Naturally food is fairly limited in the jungle but we still managed to cook fine meals of chicken and fish served on rice which grows abundantly in the forest. Bananas were everywhere and we generally managed to find a giant pineapple every day or two. We also ate more exotic meals of monkey, chimpanzee and elephant which were all delicious.

The jungle was incredible. As we walked we were engulfed in swarms of huge, luminous butterflies while numerous species of monkey played in the trees towering above us. The jungle itself was a powerful combination of greens and browns with massive trees dripping with orchids and creepers interspersed occasionally with giant groves of wild bamboo. Occasionally we would find trees and undergrowth torn to shreds with giant forest elephant footprints indicating the guilty party. Now and again we would come across giant rivers where we would lie for hours in the cool water keeping an eye open for crocs while we bathed and washed our clothes.

This part of the forest is home to thousands of pygmies and they would bring us bottles of wild honey which we learnt to eat with everything and which we used to make honey tea. The pygmies as well as the other forest peoples are famous for their drumming and most nights we would fall asleep to a distant throbbing beat. Interestingly, the tiny mud churches found in every village have totally integrated drumming into their ceremonies with singing, preaching and praying all accompanied by electrifying drumming. Every morning we would invariably be woken by the beating of drums or metallic objects summoning the villagers to the daily sunrise service. If the Congo was known as the Heart of Darkness, its multitude of churches - two or three in each tiny village - made it seem more appropriately the Heartt of Lightness!

After about a week we reached the giant Ituri River where we camped and later explored upstream where we discovered the traditional fishermen hard at work in the mighty rapids. These guys used cone-shaped fishing traps made with vines that were positioned in the powerful rapids with the openings facing upstream. The jets of water would then shoot fish into the traps which were emptied by the fishermen who risk life and limb clambering amongst the rapids. The village women would then prepare these fish in a delicious, spicy sauce and would sell portions wrapped in giant forest leaves for $0-10 each. All along the route we bought peanut butter, rice, sugar, banana fritters and fresh vegetables all packaged efficiently in these giant leaves which, when opened, made superb plates.

After another 5 days or so we reached the largish town of Bafwasende where we ate our first bread in 10 days and where we feasted on locally made biscuits and dough balls fried in palm oil with dollops of peanut butter and honey. Mmmmmmm! In Bafwasende we said a sad goodbye to our two bicycle guys, Mozanga and Rodeo, who had taught us French and become good friends. The harshness of the existence in this part of the world is illustrated by these two who have to work as bicycle traders for a year and use that money to pay for school the next year, alternating between a year at school and a year on the road for their entire school career.

Rodeo and Muzanga, Bafwasende, DRC

This region is rich with diamonds and we were repeatedly offered diamonds for our shoes. However we, like the locals, soon realized that walking with shoes is a lot more comfortable than walking with diamonds (even if the diamonds had been on the soles of our shoes...) and so didn't get any. It appears though that diamonds were more important than human rights and democracy. It took the world's longest, most cleptocratic dictator backed by the minerally obsessed West to turn this country, so rich in minerals, fertile land and hydro-electric potential, into a country devoid of basic services, infrastructure and hope to an extent we've not found anywhere else in Africa. Revealingly, Mobutu was invited to the White House by Ronald Reagan who called Mobutu the "voice of reason and goodwill in Africa"!

From Bafwasende we walked the last 24km to the village known as 238 which is the distance it is in kilometers from Kisangani. Here the road improved and vehicles were again able to travel and so we caught a bakkie to Kisangani. After a horrendous trip through the night, repeatedly getting stuck in mud-holes and breaking down we finally arrived in Kisangani ending our first month in Congo.

When we arrived in Kisangani we immediately proceeded to the Olympia Hotel, which in previous years used to be a veritable hub for travellers making the Trans-African crossing. Nowadays, however, travellers have been scared away by the riots in 1993 and the revolution in 1997. The staff were therefore particularly happy to see us, and they allowed us to camp in their large yard at the back. In one of its typical rundown African toilets, there was a piece of inconspicuous graffiti written in 1992 which states:

"Where Logic ends; Zaire begins"

When we first came across this statement, we hadn't had any experiences to indicate that its message could be extended into the emerging country of the Democratic Republic of Congo. That was, however, all about to change!!

It all started when we went to check in with all the requisite authorities in Kisangani. Any tourists visiting Congo have to register with not only the local immigration authorities but the national A.N.R. (civil intelligence) offices as well. This we dutifully did, and at the ANR offices we were greeted with a particularly helpful chief who informed us that we would be able to get a lift on one of the riverboats leaving in a couple of days for Kinshasa. It seemed he knew the commandant of the boat and would try and organise everything for us. He also informed us that in this new country, tourists are extremely welcome and we should feel free to take as many photographs as we wanted.

Acting on this advice we decided to go down to the mighty Congo river and catch a few snaps of the pirogues making their way between the two banks. Five minutes after pulling out our cameras though, two policeman approached us and asked us for documentation. They then, ever so friendly, led us up to the district military office and proceeded to question us. The office was straight out of a movie set, with decaying walls and rotting ceiling rafters enhancing the ambience of a sultry interrogation room. In the offices we watched as various soldiers strode in proudly, with cigarettes drooping out the side of their mouths and huge machine guns hanging loosely from their shoulders. The most disconcerting thing though, was that a large number of them were below the age of thirteen and judging by their look and the way their comrades responded to them, it was evident that they had obviously been in war before.

Anyway, here the three of us sat getting more and more frustrated with the barrage of inane questions that everyone was wanting to ask us. ("What is your mission here?" - "We are tourists" - "How can you prove that you are tourists?") After struggling with these questions for a while and wishing that we had got tattoos across our foreheads stating "This man is definitely a tourist", the mood was changed a bit when we were ushered into a larger office and confronted with an extremely intimidating looking soldier. We only found out later that this man was actually an agent in the special branch who had been called out to deal expressly with our case.

He seemed to know everything there is to know about interrogation, including having only one light source illuminating you from the side and a fan slowly rotating in the corner of the room. He first questioned all three of us together, and when he realized he was getting nothing, he proceeded to take us on individually. Apart from inducing a slight tinge of fear in us and almost taking us to the point where we would be willing to confess (to what we don't know), his brilliant interrogating skills left us in absolute awe of this commandant behind that big solid desk.

After four hours of interrogation they finally escorted us back to our hotel, now about ten o'clock at night, and we retired to our sleeping bags absolutely exhausted.

Two days later we boarded the riverboat to Kinshasa and set up our tents in a prime position right on the front of the main tug. As to be expected though, the boat was delayed by two days, but we consoled ourselves with the thought that we would soon be out of Kisangani and its bizarre military set-up. Five minutes before it was due to leave though, an ANR official gets onto the boat and tells us that the commandant of the river (whoever he might be) doesn't want us travelling on this boat. In a rushed and needless to say extremely infuriated fashion we packed up our tents and disembarked from the ship. As we walked away from the dock, we heard the characteristic sound of the hooter as the boat proceeded to depart from the port. An inordinate amount of profanities were subsequently thrown at both it and Kisangani.

That night was the African Cup of Nations semi final, and we went down to a local bar to loudly support South Africa as it trounced the Democratic Republic of Congo. It was sweet revenge after the harassment that we had been subjected to by the military.

So once again we found ourselves back at Hotel Olympia struggling to find a way out of this cursed town. Conrad's "the horror, the horror", was starting to slowly creep over us. After checking the port the next day we found out the bad news that no ships were due to leave within the next three weeks. Our last hope seemed to be the name of a Gambian we had been given by one of his compatriots we had met in the jungle. Yaya Sammeli who worked in the local market at Kisangani proved to be an absolute gem, informing us that our only option would be to make our way on board pirogues all the way down the river to Bumba, where we should be able to pick up another riverboat to Kinshasa. Pirogues are essentially dugout canoes which are made by hollowing out the inside of a huge rainforest tree.

A couple of days later and we found ourselves on board one of these, being paddled down river towards the first village of Ishangi. We drifted down the river until about ten o'clock that night, at which stage the paddler decided to pull into one of the inlets and sleep for the night. Five o'clock the next morning and off we were again, drifting on the immensity of this awesome river. It is a body of water that has the width of up to 30km, and yet it still has the strength to flow at around seven kilometers an hour. We were in fact informed by our ambassador in Kinshasa that a hydro-electric scheme is currently underway, which when completed will be able to not only supply all of Africa with electricity but also all of Western Europe!!

500km by dugout canoe down the Congo River, Dem. Rep. of Congo

It certainly is one mean river, and when you are floating down it in basically nothing more than a log with the sight of an imposing jungle continuously framing your vision, you can't help but feel overawed with Congo's natural beauty. We spent six days involved in this activity, hitching rides on different pirogues from each of the little villages found scattered along the banks of the river. In each of the villages we were treated to that typical display of rural Congo hospitality, and of course that ever present sound of drumming. As far as the pirogues went, we worked out how it is possible to enjoy an extremely peaceful night's sleep rolled up in your sleeping bag with the river gently pushing you forward. The serenity of waking up at half past twelve in the evening to the sight of a full moon illuminating the river and the surrounding forest is definitely a spiritual experience.

After six days we finally arrived at the large town of Bumba, 500 kilometers from Kisangani. We checked ourselves into a cheap hotel and enjoyed a welcome night's sleep on board good old terra firma. The following morning greeted us with the extremely pleasing news that a riverboat was leaving that afternoon for Kinshasa. Just as we were about to board it though, the military (this time it was DEMIAP: counter revolutionary intelligence) got wind of our presence and invited us into their offices for another friendly chat. Thankfully they were more reasonable than the Kisangani gang, but they still detained us for over an hour, searching our baggage thoroughly and asking the exact same questions. Finally we were allowed to board the boat, which had in fact been held back specially for us.

Amidst great cheering (the passengers had obviously worked out that we were responsible for the delay), we stepped onto the boat and set up our tents on the main tug.

A riverboat is essentially a large tug which pushes a collection of barges in the front of it. The Lonely Planet describes these oddities as a floating village, and that it certainly is. There are between 500 to 700 people on the barges, complete with all their produce that they are taking to Kinshasa to sell. This produce ranges from the mundane like bags of maize and sugar right through to the absolute bizarre. This latter category includes live crocodiles, turtles, monkeys, parrots and a variety of smoked animals including fish, snakes, leguans and monkeys (extremely eerie to look at). Although the bizarre category certainly added to the visual scenery of the boat, it was the ordinary farm animals that gave it the auditory experience. These animals included your typical African roosters, goats and our favourite animals, the pigs. Pigs, it seems, have an annoying habit of letting out bloodcurdling screams whenever they are either being forced to do something they don't like or simply when having sex. We got to know the sexual habits of a pig intimately, as we would often be woken up at four in the morning to the loud yelpings of pigs copulating in the front of the boat.

If it wasn't the pigs, then it was the rooster doing his thing in the early morning, or on a couple of occasions, a man right outside our tent at five in the morning telling his baby a story loudly in French. This man was just one of many of the strange characters that we came across on the riverboat. There was also an old and extremely slender man who we came to dub the "chair-snatcher", as he would pounce on any opportunity, when you got up from your chair to fetch something, to simply remove it from your possession. Then there was one member of the crew who was able to speak fairly fluent English, except it was unfortunately not regular English but the highly esteemed American variety. It is another one of those bizarre peculiarities of the Congo, that people are now not only interested in speaking English, but what they consider to be the entirely different language of American English. Throughout the country one comes across private schools charging people copious amounts of money to learn the specific rules of this new language. People who can speak English fluently will pay up to U$10 a lesson to learn that one needs to pronounce the "t" in water as a "d". You aren't supposed to say "yes" but "Yea right". It really is a strange experience to find people in the Congo proudly telling you in a put-on American drawl that they can speak both English and American English. All we can say is Yeah Right!!!!!

Anyway to get back to the boat, it proved to be our home for 16 days, even though we were assured by the captain that this was an express variety and we would be in Kinshasa in 5 to 8 days. Cruising down the mighty Congo on board this massive conglomeration of metal, people and animals proved to be an extremely interesting experience. Our days would consist of waking up early, usually sometime round half past five, stumbling down onto the barges and almost tripping over the array of pots and racks of smoked fish in order to secure our batch of freshly fried mandazis. Mandazis are balls of dough which have been fried in hot oil, and together with a dollop of peanut butter they are simply heaven in the morning. After enjoying our coffee, we would then attempt a bucket shower, which we had to do by firstly pulling up the water from the side of the boat and then fighting with the rest of the crew to get our time in the shower compartment. After that activity we would be faced with the sun and the heat, which we would try and avoid by retreating into some shady corner of the boat making sure it was far away from Gabriel the chair snatcher.

As evening approached we would cook our sumptuous dinner of rice in an awesome sauce consisting of tomatoes, onion, garlic all fried up with peanut butter, bananas and sometimes pineapple and fish. Unbelievable!!!

This daily ritual would sometimes be broken by one of Congo's equatorial rain storms, in which case we would have to find ways of keeping water out of our tent, or by our arrival at a new town. Arriving at a new town always involved some little excursion to the military, which as you can imagine is not always that pleasant an experience. On the second night in fact, we had to contend with a drunk military commander who at one stage had his hand around Lance's throat. We dealt with it!

One of the barges attached to the riverboat, DRC

The first major town after Bumba was Lisala, where one can see the imposing structure of Mobutu's grand house overlooking the river. In this new era though, the military have simply taken it over, and appropriated all the furniture for their own offices. Needless to say, its a rather absurd experience being interrogated while you are lounging on a chic Italian lounge suite looking at a commandant sitting behind an ebony desk inlaid with gold trimmings.

After Lisala it was off to Mbandaka where we stayed for three days before heading off for Kinshasa. About 200 kilometers out of Kinshasa the omnipresent scenery of the jungle gives way to rolling mountains, and with the corresponding narrowing of the river, you get the impression that you are now cruising down the Rhine. The military soon end that illusion though. We had to deal with them again at a place about 60 kilometers outside of Kinshasa. This place in fact turned out to be the previous playground of Mobutu, complete with two supertubes, a high diving board and an olympic size pool. The thought of a seventy year old dictator whooshing down a supertube just enhances the absurd vision we already have of the previous Zaire and present day Congo.

Finally we arrived in Kinshasa and set about trying to find a hotel for three dollars a night. Unfortunately this city is one of the most expensive in the world, with a night in the Intercontinental setting you back over U$170. Obviously we weren't going to stay there, but even in our customary budget category, there wasn't a hotel to be found for under U$8. Fortunately our embassy proved to be extremely helpful and we ended up staying in the house of a local who works there. He lives in the downtown Cite area which is basically the townships of Kinshasa, packed with all the vibrancy and spirit that one would expect to find in an area like this. About two million people stay in this area, and we have been treated with extreme hospitality and on many occasions simple celebrity status. The family we are staying with are extremely friendly, and although they can't speak much English, we have found out that we have actually acquired a fair knowledge of French to help us get by.

The embassy staff have also been extremely receptive towards us and almost every night we have been treated to a fantastic meal. On the Thursday the Charge d'Affairs (essentially the ambassador) treated us to drinks and huge pizzas at the Intercontinental giving us all the information on the politics of this region. He contextualised a lot of our experiences by telling us that a great deal of the places we passed were in fact the famous refugee massacre sites. Naturally the army were a bit edgy about our presence there, particularly since there are also a number of rebel groups and foreign mercenaries still hiding in the jungle.

The Friday night was spent polishing off half a bottle of whisky with Johann, the person in charge of most of the South African embassies' communication links around the world. Saturday was spent at the administrators house consuming copious amounts of food and drink while watching videos and cricket. That day also saw the arrival of Kingsley Holgate, who for those of you who don't know, is the adventurer who is attempting to cross from the mouth of the Zambezi to the mouth of the Congo river. He is an extremely amiable man, and we spent many long hours swapping stories of our different adventures (and he's also become an African Wanderers e-mail subscriber). On the Sunday we were at Helena's house, the person in charge of the visa section, swimming in her pool and enjoying a sumptuous roast dinner. Monday night we had off, but on Tuesday night back we went to Helena's house for another great dinner of South African trout, fruit salad and Hennessy Cognac. Once again we sat around till half past one in the morning discussing adventures and South Africa's future with Helena, Kingsley and Ian, a British security agent working in Kinshasa.

Anyway, after all this culinary and intellectual stimulation we once again find ourselves preparing to head off for our next far-flung destination. The next two weeks should see us making our way up Congo-Brazzaville, traversing another section of equatorial rainforest complete with its own set of bad roads and bad soldiers. We're finding these rainforests pretty tedious now, and we are starting to hanker after the cooler environments of North Africa's deserts. One thing's for sure, the desert definitely won't have humidity like this. After Congo-Brazzaville it is straight onto Cameroun with its stretches of beautiful beaches and relative security. No more Guys with Guns, hopefully!

So here we are in sultry Kinshasa having successfully traversed the Congo from East to West, and acquiring the title of the first travellers to have done that since the war began in 1996. This just proves that we are dedicated to bringing you the reader, the best possible tales of adventure at a cost which simply cannot be beaten by anyone else. That cost is a simple e-mail each month, and there are some of you (you know who you are) who are reneging on the deal. If you want to read about our hapless wanderings through Congo-Brazzaville and the entire West African region, then we suggest you get typing. If you are especially vigilant in your correspondence you might even be lucky enough to receive one of our highly sought after audio tapes giving you a wacky sound experience of our adventures. Act now, stocks are limited!!!!

Please address all replies only to: africandave@hotmail.com

We've attached a copy of an e-mail written by Joe, our travel companion for the last 2 monthsmonths (who's flying home and will be sending this email for us), so that you can read about what we've been up to from someone else's perspective.

lots of love

the African Wanderers

Dave and Lance

Joe's message :

As I am writing this, I am, sitting on a wicker chair on the third floor deck of a tug boat which is pushing three barges down the Congo River. The trip is everything I expected and less. One thousand people are living (cooking, bathing, sleeping) on top of the merchandise (corn-maize, smoked fish, wicker chairs, etc... ) they are planning to sell in Kinshasa, Congo's capitol. The passengers on the boat are the merchants of Congo. From where I sit I can see a rolling checkerboard of coloured plastic tarps, propped up by poles, tented over the barges, protecting the passengers from the sun and the rain. There are pirogues (canoes dug out of a single tree) crossing the river towards us. The two paddlers of the pirogue stand, one at the front and one at the back, and propel the boat through the muddy water with long thin paddles. They live in the local villages along the river and sell food and merchandise (charcoal, smoked fish, live pigs and crocodiles) to the boat passengers. Every day is another scene of some weird thing that I do not understand.

Dugout's from riverside villages pulling up alongside to sell their smoked snakes, fish and monkeys

Every few days I remind myself to enjoy this wonderfully, unusual experience. I need reminding. Right now, I just want to get off of this boat and out of this country. The trip has been a bit of an endurance test. We originally figured three weeks to traverse the country. We are on week eight now with another week to go (I hope). When I negotiated my spot on the barge, the Captain told me it was an express boat and would arrive in Kinshasa in 5 to 7 days. That was 6 days ago and his answer has not changed. He still says we will arrive in 5 to 7 days. "But Joe," you ask, "how can this be ? " That's just the way things are here. I started a pool with the rest of the crew where they could buy guesses as to when we arrive.

Midway through the trip, I decided it was time to come home. By the time you receive this, I expect I will be in Europe where I hope to spend a couple of weeks.

But lets start at the beginning, shall we. When you last heard from me I was in Kampala, the capitol of Uganda, and still quite excited about my trip. From there, Lance, Dave and I took a bus to Congo's Eastern border.

In order to get to Kisangani to catch a river barge, we travelled 500 miles overland through the 2nd largest rainforest in the world. On the Eastern border of Congo (formerly Zaire) are the "Mountains of the Moon," home of the Mountain Gorillas and bamboo which grows at one meter per day. The mountains are covered with thick jungle growth and look like they were created by Disney for the King Kong movies. The jungle we travelled through looked and sounded like the jungles of the Tarzan movies.

The only transport available for the first two hundred miles were supply trucks carrying goods to various points in the jungle. The driver piles goods on the back of a pickup truck way above the height of the cab and then he secures it with a tarp and ropes. Then he piles more people on top than you could ever imagine. Everyone hangs onto a rope and each other as if riding a bull at a rodeo. As is usually the case with rural Africans, everyone laughs all the time as if it is just another funny adventure. Every time I thought I had had enough, I would look over at the Big Mama next to me breastfeeding her baby and she would laugh at me and I would remember that I choose this.

A couple of times the truck reeled over so far that half of us spilled off into the growth on the roadside. Of course, everyone would laugh and climb back on. Every few hours the truck would get stuck in a three foot deep mud hole, which I previously considered impassable. We would climb down and push it through, or dig it out, and off we would go.

Every so often we passed one of the small villages which lined the route and watched the same interaction unfold. A villager, who looked up to greet the truck roaring by, was shocked to see three Muzungus riding on top. The children ran out to the road waving hello with both hands in front of them shouting " Muzungu, Muzungu." Everyone on the truck would laugh, I felt like the guest of honor in a very small parade.

A 130 mile stretch of road was impassible by truck but bicycle taxis hauled goods through. So we hired Mozanga and Rodeo, two 18 year old locals, to carry our backpacks on their bikes while we walked 130 miles in 12 days. We paid them $100 which will pay for 10 months of their tuition at Kisangani University.

As we slowly walked past a village, we watched the same surprise and slack jaw stares as before but with much more hesitancy from the villagers. Usually someone was bold enough to say Jambo (hello) and then a Mama would yell to her children or neighbors to come see the Muzungus. Several times a family would step out to the road and greet us and give us a papaya. Dave would talk to them in Swahili and they would laugh and squeal because the Muzungus knew their language. The children were too shy to approach more than a few steps without their mothers around. The infants would start to cry if we took a step towards them, while everyone else would laugh. On occasion, I would glance back over my shoulder after we had passed a village to see 10, 20, sometimes 40 Congolese in the road staring at us walking away.

Each day we would stop to swim, bathe and wash our clothes in a river along the way.

At the end of the day, we would pitch our tents in one of the larger villages. From the moment we arrived until we left we had an audience. Tent construction drew between 15 to 40 each night. The highlight of the show is the elastic connected poles snapping together on their own. And of course the dome rising out of a flat piece of material always generated plenty of ooh's and ah's.

One night the crowd was especially large, loud and close. Lance, Dave and I retreated into one tent to escape the throngs. We stayed in there sweating and listening to our fans for close to an hour until the crowd thinned out. Then we crawled out and began to cook dinner.

We brought some food with us but mostly we bought food in the villages. We would eat papaya, banana, and tea for breakfast. For lunch, banana, pineapple and fried manioc (tastes like a dry potato). Dinner consisted of locally grown rice with meat; rice with chicken, or rice with antelope, or rice with elephant, or rice with chimpanzee. You know, whatever the pygmies found in the back yard.

We waited in one village (Bafwasende) for several days for transport. Several times a day we would walk to the outdoor market and past two houses (mud huts with thatched roofs) where two little girls lived. As we approached we would see them by the dirt trail in front of their houses watching for us. As soon as we made eye contact, they would run screaming into their house and slam the wooden front door and peek out until they saw we were safely past. Then they would come out and sit near their amused mothers and stare at us.

After six days I had had enough of walking. The landscape was the same each day and I was tired. Each morning I would attempt and fail to rent a bicycle. Each day I would walk another 12 miles. Eventually we made it out of the jungle and after a gruelling 24 hour pickup truck ride, we arrived in Kisangani; restaurants, ice cream, and television. We were very happy. And then we met the military.

I could tell you the a couple of long stories (and they are good ones), but it wouldn't be enjoyable right now. I am still in it. Suffice to say that during the past 7 weeks I have been interrogated seven times, had my bags searched three times, given a written statement twice, been escorted by soldiers with machine guns, handgrenades and rocket launchers more than a half a dozen times. I watched a Commandant hold his pistol to the head of a ten year old boy that he suspected was a thief. As a bonus, the soldiers have asked for "une cadeau" (a gift) after each of the above cultural activities.

As dramatic as all that sounds, we were never at risk, but still, I was scared plenty of times. The reason for the hassle was two fold. First, it is a time honored tradition here for military men to shake down Muzungus for money. Congo has one of the worst reputations for bribery and corruption. And when the military sees, us he sees money. Secondly, Congo just had a coup d'etat during which white mercenaries were hired by the old government to fight the rebels. So when three white men with crew cuts (Dave and I are both sporting flat tops) rock up into a town with exotic gear for surviving in the jungle, the military become a bit suspicious. So they haul us in to see our papers, ask us the same questions over and over and make us wait for hours.

So that has been a bit tiring and it is almost over (I have been saying that for over a month now).

Meanwhile, before the fun started, I was in Kisangani expecting to be on a boat and out of Congo in a weeks time. 11 days and many hours of interrogation later, we were still in Kisangani with no boat in site. We were going stir crazy and wanted to get out of there and away from the military, so we arranged a ride in a pirogue (dug out canoe) to a small village 50 miles down river. From there we planned to hire another pirogue (and two paddlers) to take us to Bumba, where we could catch a barge to take us the rest of the way to Kinshasa. Six days and five pirogues later, we drifted into Bumba. We slept and cooked on the pirogues and bought supplies from the villages along the way.

We had good luck in Bumba. A boat was leaving for Kinshasa the day after we arrived. So we rushed to do our food shopping, pack our gear and get on the boat. Of course the military spotted us and hauled us in for a few friendly hours of questioning. Fortunately, the chief of Immigration for the port detained the boat and all the passengers for us. When the military let us go we ran down to the dock and the barge departed two minutes after we stepped on board.

We should be in Kinshasa in a week (or three). When the boat stops at a town along the way, my heart skips a beat in expectation of the military hassling us. We have performed the scene so many times now but the thrill is still there.

My experience on the boat has been so strange that it is difficult to only write a few lines. The boat is packed with people and like people all over the world, most of them are crazy. They all want to be my friend and ask me for money. Some days are great; relaxing, scenic, interesting. Other days I stay away from the guard rail because I am tempted to jump overboard and swim to shore just to get off the boat.

Lance had Malaria, but besides that our health has been good.

One great bonus of the voyage is that I have learned to speak French. Because Congo was a colony of Belgium (where mostly French is spoken and some Dutch), the Congolese speak French, in addition to their tribal language (and there are over 500 different tribal languages). So through all of the above, I stumbled to communicate in French. Except with the military, where I let Dave speak Swahili.

Here is your thirty second history of Congo (formerly Zaire). It is taken from the Lonely Planet. Congo is home to over 100,000 pygmies who still live as hunters and gathers in the densely forested areas. It is named after one of the first great Kingdoms to rule in the 14th century. The Portuguese were the first Europeans to trade\raid the interior taking slaves and ivory. In 1874, the British journalist Henry Stanley, who after taking his historic voyage in search of David Livingstone, continued into the interior of Congo.

Belgium formally laid claim to Congo at the Conference of Berlin in1884 when the European powers drew lines on a map of Africa, dividing it up into their colonies. While the King of Belgium, King Leopold, remained the sole owner of this vast territory (as large as the USA east of the Mississippi), its inhabitants were subjected to one of the most preposterous forms of foreign domination Africa would ever know. When the news of the worst atrocities leaked out, King Leopold was forced to hand over the territory to the Belgium government. Colonial administration by the Belgium government, however, resulted in little real change.

Joseph Conrad's novel, The Heart of Darkness, was set on the Congo River. Kurtz, the main character, who worked for "the Company" collecting ivory, exclaimed on his deathbed, "the horror! the horror!" The book is mandatory reading for all visitors to the area.

Belgium gave Congo independence in 1962 as freedom was sweeping through Africa. They were ill prepared for self rule and in 1964, General Joseph Mobutu seized power, changed the name to Zaire, and ruled until he was overthrown last year by a rebel force.

Mobutu was one of the worst dictators in Africa. He amassed a huge fortune while most Congolese live in poverty. He received his fortune by selling off mineral rights and pocketing aid given to him by the West. He spent $15 million to sponsor the "Rumble in the Jungle", the world championship fight between George Foreman and Mohammed Ali in 1974. He had his European hair stylist flown in every two weeks to cut his hair, at an estimated cost of $5,000 each trip.

America supported him because we needed an ally to serve as an arms conduit for the war in Angola. Angola had a popular Communist government and we did not like the thought of Communism sweeping through Africa. So we supplied arms to rebel forces in Angola to fight against the government. And we needed Mobutu in order to ship the arms there. For years, Mobutu was the only Sub-Sahara African leader to be invited to the White House. Reagan called him "the voice of reason and goodwill."

Aid was cut off in 92 after the Cold War and our interest in Angola ended. Zaire's economy crumbled and Mobutu did not pay the military (or any civil servant for that matter) for years. He was overthrown last year by a popular based rebel force led by Lawrence Kabila. Kabila changed the name of the country back to the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Congo is rich with resources: copper, cobalt, gold, diamonds, timber, abundant sources of hydro power and land for agriculture. Yet it is one of the poorest countries in Africa. Per capita income is $180 (per year). There are virtually no asphalt roads, only two rail lines, and, except for the capitol, no phones.

Well, that is it for your history lesson and my letter.

With love,

Joe

29 April 1998

Hi everyone

Well, we've finally made it through the terrible Central African region with its wars and military dictatorships into a relatively democratic and stable Cameroun.

A few days after we last wrote we left Kinshasa and crossed the Congo River to Brazzaville, the capital of the neighbouring Republic of Congo (not to be confused with the Democratic Republic of Congo!). Unlike the former Zaire, Congo-Brazza (as it is also known) is still at war. Fortunately for us the French-backed rebels of Denis Sassou-Ngessou had ousted the democratically elected President Lissouba from the capital and the war is now being waged in the West of the country. However, the prospect of now leaving the former-Zaire (which had at least finished its war) and beginning a journey through a country which is still in the midst of one didn't really appeal to us much. From the frying pan and into the fire, so to speak.

After an hour our boat had crossed the river and we were in Brazzaville. After doing the necessary immigration formalities and dumping our bags at the Catholic Cathedral (where we found a room to sleep) we began exploring this beautiful city.

At least it was once beautiful...

After the four months of war waged in the streets of Brazza, every building is riddled with bullets and mortar craters. Beautiful tinted glass skyscrapers have been shattered - we could actually see right through one of them - and even the giant Basilica church is in ruins. As we wandered the completely deserted streets we spotted a chic mini-mall and went exploring inside where we found the Air Portugal offices completely destroyed with the floors covered with pools of dry blood.

Bombed out skyscraper, Brazzaville, Rep. of Congo

Happily, one of the buildings that suffered the worst damage was the Elf Tower. This company was largely responsible for the ending of democracy in Congo as it funnelled funds to the rebels in exchange for a massive oil contract in this oil rich country.

Two days later we were out of Brazza on board a giant truck going North through the beautiful, fertile Savannah area on our way to the town of Makoua where the rain forest begins again. There we were dismayed to hear that the road to Cameroun no longer existed and that we would have to walk another 170km through the jungle. Perhaps only Joe can understand how much that prospect didn't excite us. Anyway, we had no other choice so after a few days of rest in the local Catholic Mission, we piled our backpacks stuffed with food on the back of a bike and off we set.

After about an hour we were in high spirits marching through beautiful countryside which gradually changed from savannah to jungle. We camped the first night in a small village 25km from Makoua and left early the next morning for the village of Mambili a further 25km away. Our bike chauffeur, David, had been acting really strangely the first day and on the second day he waited for us to go on ahead and then dumped our luggage in a small village and disappeared: not before helping himself to Lance's walkman, some money and half our food.

As a result we were forced to spend the night in the picturesque village of Itagniere where we managed to buy some freshly killed antelope which we ate with rice which was about all the food we were left with. The next morning we spent relaxing, waiting for the rain, that had followed the most powerful thunderstorm we'd ever witnessed, to end.

Jungle village of Itagniere, Rep. of Congo

Due to Congo being one of Africa's most unpopulated countries the villages here are tiny when compared with those in the jungle in Congo-Kinshasa, consisting normally of just a handful of families. Each family has their own hut/s and a few families will share a communal cooking/relaxation area which is roofed-over but has no walls. This is where we would normally cook and share our tea/coffee with the village elders in the morning. (Our ex-chauffeur had kindly taken our porridge so we generally ate only one meal a day which sometimes we were able to supplement with fruit growing in the villages.) The area around both the huts and the communal areas are meticulously swept of all leaves and rubbish every morning leaving a clean, sandy village that contrasts sharply with the damp, dark jungle that threatens to engulf it at any moment.

After the rain stopped we found another bike and set off at a good pace for Mambili for the 2nd time. Unlike in the Congo-Kinshasa jungle where at least there was a semblance of a road, the path through this jungle was completely overgrown with vines grabbing at us, brambles hooking on our clothes and no sunshine penetrating the dense foliage. As we walked further we found huge trees that had fallen across the road making passing difficult.

As we walked we were joined by a short, drunk guy (we were sure he was at least part pygmy) who helped us get our bike across the 12 bridges that were no more than two or three 10cm wide poles on which we balanced precariously. We said goodbye to our chauffeur when we reached the massive Mambili River where we found the ferry had long since sunk. This was where our short friend (his name was Zico) came in. He agreed to paddle us across in his little pirogue one by one. So Dave climbed aboard with his backpack and hadn't got more than 2 meters from the riverbank when the pirogue promptly sank, soaking Dave and his backpack. Crying with laughter we watched as the absolutely mortified Zico managed to refloat the piroque and apologised profusely having committed the piroqueman's ultimate error with the his most distinguished clients ever. We eventually made it across and then hacked our way through tall grass until we reached the village. This was one of the smallest on the whole trip with only two families inhabiting it. Naturally, being the bizarre Africa we love, due to some disagreement these two families were not speaking to each other!

Zico's big moment...

Oh dear...

We camped here for two nights as we couldn't arrange a bike for our luggage. We didn't mind the delay though as it gave us time to explore this powerful, mysterious forest as we sat for hours just watching the amazing variety of creatures going about their lives. We eventually arranged a bike with a passing chauffeur and set off early the next morning on our way to Epoma. The path continued to deteriorate with fallen trees across the path about every kilometer but after 5 hours we'd covered the 22km and arrived in the fairly large village. We were really fortunate to be able to buy 5 cups of rice which eased our food problem considerably as did the 5 eggs that were given to us which we scrambled the next morning. Hmmmm! The villagers got one of their hunting dogs to catch one of the very nimble chickens which we feasted on. We ended up eating 6 whole chickens between the two of us in a week!

From Epoma the path becomes so overgrown that bikes can't pass so we paid two pygmies to carry our bags to the next village. One of the pygmies had a baby monkey that sat on top of his head as he walked, screeching every time he put it down. Its mother had been killed and eaten by the pygmies and as it was too young to care for itself they were raising it. The hunting of monkeys is so widespread here that, unlike in the Congo-Kinshasa jungle, there were no monkeys playing in the trees as we walked as they either hid from us or had been eaten. There were tons of butterflies though which swarmed around us like a living rainbow.

The "Great North Road", Rep. of Congo

We would pass small streams every day where we would swim and wash ourselves and our clothes. Lance learnt about the hazards of this natural living, though, when a fish latched onto where it hurts most sending Dave into uncontrollable laughter as Lion stared worriedly at his wounded weapon. Don't worry ladies, he has made a complete recovery.

The next few days passed pretty smoothly except when we couldn't find anyone to carry our bags forcing us to carry the 30kg loads about 26km. One pair of puny pygmies who carried our bags literally jogged all the way as we stumbled behind, having had a few slugs of deadly maize spirits "for morale" as the locals put it.

After about 150km we reached the village of Ibonga which was the last before we reached Liouesso where the road began again. We organised two porters to carry our bags the final 22km and set off. After 14km the two guys sneaked off after having stolen most of what was left of our food and Dave's torch (sorry Sonja and Bieq's!). Two thefts two Sundays in a row!

We finally arrived in Liouesso after 9 days walking and were given a hut to sleep in by the chief.

The next day we caught the bakkie to Ouesso, 80 km away. The vehicle was not only piled high with people but also a range of dead animals including 5 monkeys, 6 antelope and a porcupine. After 60km we were stopped by the military who hauled us off in their vehicle to Ouesso where our bags were searched thoroughly and our passports confiscated.

We spent the night in the catholic mission and went down to the Immigration offices the next morning where we successfully recovered our passports without paying the bribe demanded of us. Then we rushed down to the river where we just managed to catch the motorised pirogue to Pokola, the home of a giant logging company and the village it has borne.

After a few hours and a few breakdowns we arrived in Pokola where we had our passports confiscated and were told we'd only see them again if we paid the necessary bribe. In the meantime we organised a lift on one of the dozens of trucks loaded with timber heading for Cameroun and were set to leave at 6am the next day. Unfortunately the police chief was playing hard ball and we couldn't get our passports back in time so we missed our lift.

Time for the African Wanderers to get tough!

We had the name of the police chief written down so Dave flashed the card of the SA ambassador in Kinshasa and said that he was his dad and that we'd happily pay the money if the police chief would just confirm that we had recorded all his details correctly. We left the office with our passports a minute later!

Unfortunately we only managed to arrange a truck lift the next day and finally reached the Congo-Cameroun border. The Congo official's bribery demand caved in under the same "ambassador's son" trick but we happily paid the $8 bribe entering into Cameroun as we had no visa due to the embassy in Brazzaville having been closed due to the war.

Four days and some uncomfortable truck rides later we arrived here in bustling Yaounde. Two days ago we met 34 Peace Corps guys and girls (!) in the foyer of the Standard Chartered Bank. They had just been evacuated from Chad and we were staying in the extravagant surrounds of the Hilton. That night they invited us over and treated us to drinks and what must rate as one of the greatest meals in 11 months. All paid for by the American government!

Last night we got an even greater treat, dancing down to the jives of the Hilton's nightclub. It was a huge rave where we both remained true to our liberation theology and impressed the girls with an outstanding display of dancing. That all ended at two o'clock in the morning, and then the big surprise was given to us. One of the girls kindly gave up her room and shared one with another person down the hall. This left a beautiful, fully kitted-out room for the two of us, with television, great beds and our first hot shower in over four months. Three nights in Yaounde and we've already organised a free night in the Hilton, the mind boggles at what the African Wanderers are capable of achieving!

Yesterday unfortunately, Lance suffered the indignity of having his wallet snatched with ALL his travel documents (passports, vaccination card...) and about $40 lost. Africa is sometimes a very difficult mistress. At the moment, Lance is considering following the policy of the Nigerian sleeping on the bridge between Kenya and Ethiopia. In his words, "I'm African mon, I don't need no passport to travel on my continent." He's still not too sure whether spending time in a Chadian jail will really be worth the philosophy though. Anyway, with or without a passport, we will be travelling down in a day or two to Cameroun's Kribi beach for a week to rest and recuperate with some Peace Corps friends. We need it! (Late news: the reward we put out got Lance's documents back. So all's well again.)

So we've successfully made the East to West Africa crossing which means we're back in e-mail territory again so all those moaning subscribers out there can expect frequent e-mails again. We hope to send out some personal e-mails soon - definitely within the next 3 weeks.

Thanks for all the messages and keep writing.

love

the African Wanderers

Dave and Lance

thank you for information..

ReplyDelete